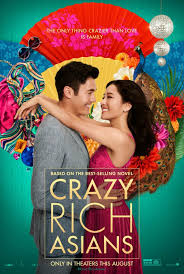

In Review: Crazy Rich Asians

By: Rev. Ted Geise

Asian film has a Christian twist

Years ago, there was a critically-acclaimed all-Asian-cast film in which Michelle Yeoh played a leading role: Crouching Tiger, Hidden Dragon (2000). This time around she plays a supporting role as Eleanor Young the protective mother of male lead Nick Young (Henry Golding) in this year’s celebrated romantic comedy Crazy Rich Asians. Nick is in love with NYCU Economics professor Rachel Chu (Constance Wu) but has kept an important detail about his life from her: he is a crazy rich Asian from a premier family in Singapore. As the film unfolds Rachel goes on a journey of personal discovery when she accompanies Nick back to Singapore for the wedding of his best friend Colin Khoo (Chris Pang) to fiancée Araminta Lee (Sonoya Mizuno). At first Rachel’s biggest anxiety comes from the prospect of meeting Nick’s family. She feels intimidated because of her single-mother immigrant North American upbringing. She quickly discovers Nick’s mother disapproves of his choice in girlfriends and, over the course of the film, Rachel seeks to find her place in the wider Asian world and in her relationship both with Nick and with his family as an Asian-American woman.

Years ago, there was a critically-acclaimed all-Asian-cast film in which Michelle Yeoh played a leading role: Crouching Tiger, Hidden Dragon (2000). This time around she plays a supporting role as Eleanor Young the protective mother of male lead Nick Young (Henry Golding) in this year’s celebrated romantic comedy Crazy Rich Asians. Nick is in love with NYCU Economics professor Rachel Chu (Constance Wu) but has kept an important detail about his life from her: he is a crazy rich Asian from a premier family in Singapore. As the film unfolds Rachel goes on a journey of personal discovery when she accompanies Nick back to Singapore for the wedding of his best friend Colin Khoo (Chris Pang) to fiancée Araminta Lee (Sonoya Mizuno). At first Rachel’s biggest anxiety comes from the prospect of meeting Nick’s family. She feels intimidated because of her single-mother immigrant North American upbringing. She quickly discovers Nick’s mother disapproves of his choice in girlfriends and, over the course of the film, Rachel seeks to find her place in the wider Asian world and in her relationship both with Nick and with his family as an Asian-American woman.

While Crouching Tiger, Hidden Dragon was extraordinarily popular it had more hurdles to jump with North American audiences then Crazy Rich Asians. Ang Lee’s film was entirely in standard Mandarin requiring subtitles throughout, and it was a period drama set in 19th century Qing Dynasty China. But what it had going for it was epic Hong Kong style wire-work action and a riveting pair of romances. As a romantic comedy revolving around a wedding, Crazy Rich Asians is more accessible to a general North American audience. While the cast is almost exclusively populated by Asian actors it is filmed almost completely in English. In an interview with Jon Turteltaub, director of The Meg (2018), Crazy Rich Asians director Jon M. Chu, who felt an affinity with the character of Rachel Chu—himself being a second-generation Asian born to an immigrant family and raised in California—explained his desire to make a film both celebrating Asian culture and bridging the Asian and Asian-immigrant experience.

This bridging is seen throughout the film. One example is its use of popular Western music sung with Chinese lyrics. More fusion than karaoke, this approach undergirds the film’s theme of a woman trying to navigate two cultures. This can be a challenging topic to address in a lighthearted rom-com when such themes are normally dealt with in heavy dramas. How does Chu tackle this? At one point about three-quarters into the film the term “banana” is used to describe someone who is “yellow” on the outside and “white” on the inside. While this small moment highlights Rachel’s personal struggle it surfaces again more profoundly during the film’s credits with the use of a lilting cover of Coldplay’s song “Yellow” sung by Katherine Ho. Chu wanted the song because of his own complicated relationship with the word yellow and the historically negative racial implications of the word’s use toward Asians. Including the song was a way of addressing this. In a personal letter to the band Coldplay director Chu wrote that, “The color [yellow] … always had a negative connotation in my life,” … “until I heard your song.” In an interview with the The Hollywood Reporter Chu, in a reference to the song’s lyrics, said, “We’re going to own that term,” … “If we’re going to be called yellow, we’re going to make it beautiful.” Essentially, he took a derogatory term and turned it into a badge of honour. To be clear Coldplay’s song “Yellow” is not originally about these racial ideas but Chu’s use of the song reframes the somewhat ambiguous romantic lyrics freighting them with new content.

At one point about three-quarters into the film the term “banana” is used to describe someone who is “yellow” on the outside and “white” on the inside.

Questions of racial, ethnic and cultural identity are woven into the film’s other driving thematic elements. For example, Rachel being poor in comparison to Nick is one point of dramatic tension capitalizing on these themes. As Rachel navigates the waters of Nick’s affluence she also has to come to terms with something she saw as a strength which Nick’s family sees a weakness: she comes from a single-mother family with no close relatives while Nick comes from an intact family (although Nick’s father is out of town on business through the whole film and only comes up in conversation) with a vast network of tight-knit relatives. What this all leads to is the most important point of contention within Crazy Rich Asians: American individualism and following your passion, basically the pursuit of happiness, versus the Asian idea of happiness coming from sacrifice, respect, honour, and long-term planning for the benefit of the family. As a result, Eleanor Young sees her son Nick’s love for Rachel as the potential ruination of the Young family as Nick is set to take over the family business.

Christian audiences may want to think a bit about how Nick’s mother, Eleanor is presented. If the film has a central villain impeding Nick and Rachel’s relationship she is it and yet in the character’s second scene Eleanor leads a women’s Bible study with her close family and friends. The Bible study includes Eleanor reading Colossians 3:1–2, “If then you have been raised with Christ, seek the things that are above, where Christ is, seated at the right hand of God. Set your minds on things that are above, not on things that are on earth.” The scene also mentions Ephesians 6:4, “Fathers, do not provoke your children to anger, but bring them up in the discipline and instruction of the Lord.” As the film unfolds it’s revealed that the Young family and extended family are Methodists. Eleanor eventually gives her approval to Rachel and Nick however Christians may find it disappointing that a character so strongly positioned as Christian at the beginning of the film ends up being the most cruel and “backward” character who must compromise in the face of romantic love in order for the film to have a happy ending. The Bible study scene provides subtext and motivation for many of Eleanor actions like having the temerity to deny permission for her son to sleep with his girlfriend under the family roof. Herein lies the disappointment, the character is set up to be a positive role model—a Christian mother who reads Scripture and has moral fibre in the face of social pressures—only to be shown as mean-spirited toward Rachel with words as sharp as any tiger’s claws or teeth.

In the end Rachel realizes she must outmaneuver Eleanor and not back down if she wants to succeed in her relationship with Nick.

How is this impasse between mother and potential daughter-in-law resolved? In the end Rachel realizes she must outmaneuver Eleanor and not back down if she wants to succeed in her relationship with Nick. An interesting aspect of the approach Rachel takes is that she seems to follow the principle laid out in Philippians 2:3–4, “Do nothing from selfish ambition or conceit, but in humility count others more significant than yourselves. Let each of you look not only to his own interests, but also to the interests of others.” Rachel’s willingness to let Eleanor win in her bid to protect the family from public disgrace and her son from losing his family for love by sacrificing any future relationship with Nick prompts Eleanor’s willingness to compromise and approve of the relationship. This is a bit of a spoiler, except for the fact that every romantic comedy has a dramatic heartbreaking impasse that must be overcome about 20 minutes before the end of the film. Crazy Rich Asians is no exception. In this, and in many other ways, Crazy Rich Asians is a conventional rom-com. Where it excels is in its final broader message of being “kind and compassionate” to one another (Ephesians 4:32) whether that’s applied to racial, cultural, or social differences.

Crazy Rich Asians, shot largely in Singapore and Kuala Lumpur in Malaysia, is one of the breakout surprise successes of the rather slow 2018 summer box-office already making $88 million in its third week on an estimated budget of $30 million. It also went from eighth place in its opening weekend (August 10 –16) to the number one position dethroning The Meg for two solid weeks (Aug 17–30). This is particularly interesting as it makes Crazy Rich Asians the third number-one film set and or shot in Asia to top the 2018 summer box-office. The other two films included the aforementioned shark action adventure film The Meg which, while shot mostly in the coastal waters of New Zealand, ended in the waters of China’s Hainan Island prominently featuring the popular beaches of Sanya City and its towering 108-metre (354 ft) Buddhist statue The Guanyin of Nanshan. Likewise, Dwayne Johnson’s action adventure disaster film Skyscraper (2018) was set in Hong Kong, even though it was filmed in and around Vancouver, Canada. Why is this important? China is the second-largest market for Hollywood films (not factoring in the rest of the Asian market) making success in Asia important to the North American film industry. With the success of these film audiences can expect more films catering to or, like in the case of Crazy Rich Asians, seeking to bridge the North American and Asian markets. As this approach advances it remains to be seen whether film makers will be “kind and compassionate” toward Western European and general North American racial, cultural, social and/or religious differences. One has to wonder how portrayals of Christianity will fare as more film makers shift their focus from West to East? Will the film industry recognize that Christianity is a religion that transcends race, culture or ethnicity as it has been from its roots when Jesus said to His disciples, “Go into all the world and proclaim the gospel to the whole creation,” (Mark 16:15)?

Rev. Ted Giese is lead pastor of Mount Olive Lutheran Church, Regina, Saskatchewan, Canada; a contributor to The Canadian Lutheran, Reporter; and movie reviewer for the “Issues, Etc.” radio program. Follow Pastor Giese on Twitter @RevTedGiese.