A Defense of Beauty: Lutherans and Church Art

by Kelly Klages

Why does beauty matter in the church?

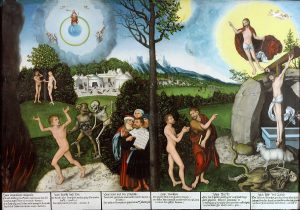

Law and Gospel by Lucas Cranach the Elder (1529).

Art is a powerful resource for teaching the faith. Beauty, order, and harmony in worship bear witness to our beliefs and reflect truth about God’s Word. Lavish art has been a hallmark of biblical worship, from God’s instructions for building the Tabernacle in the Old Testament to the heavenly visions of worship in Revelation. The early church adorned worship spaces with intricate paintings and mosaics even before church buildings became legal and common. For millennia, stunning visuals have set places of worship apart as the most important structures in their communities. The sanctuary visibly witnesses to what is believed and taught there, its beauty an offering to the glory of God.

“That’s Too Catholic!”

I grew up in a Baptist church where sanctuary pictures were feared to be “idolatrous.” Growing up evangelical, it was assumed that visuals we didn’t use—visuals that could be seen in a Catholic church (like crucifixes)—were simply wrong by default. Conversion to Lutheranism in my early twenties cured me permanently of this irrational phobia.

This aversion to images, still rampant in Calvinistic and evangelical churches, dates back to the 16th-century iconoclasts that came after Martin Luther. Luther strongly opposed these radical reformers. Instead he encouraged churches to retain whatever was good, beautiful, and beneficial for proclaiming the Gospel. Art is not idolatry; we don’t worship images, but our Creator.

Lutherans viewed themselves as the Church Catholic rightly reformed, not as a novelty sect breaking from historic Christianity. So it is no surprise that historic Lutheran churches, first in Europe and later in North America and elsewhere, share much of the same beauty and grandeur of the Roman churches. Our Reformation was, and remains, deliberately conservative: fix what is wrong, and if it ain’t broke, don’t fix it (or break it). Vestments, stained glass, statuary, chanting, incense, crucifixes, and other art forms are just as distinctively and historically Lutheran as they are Catholic, and our confessions point out that they are acceptable to use in Christian freedom.

Art is not idolatry; we don’t worship images, but our Creator.

One major reason why traditional Roman Catholic, Eastern Orthodox, Lutheran, and Anglican churches are so beautiful and artistically lavish, is the recognition of the true body and blood of Jesus in the Lord’s Supper. Despite differences on our understanding of the real presence, there has been some level of agreement that Jesus is literally present with His saving power in communion. That has implications for our understanding of what church buildings are for: the gathering of believers is in a sense no less than heaven on earth, the throne room of God. Art reflects what is believed. On the other hand, if a church body believes that Jesus is physically far off, and that worship comprises a moving music experience and a Bible-based lecture, the surroundings and aesthetics will inevitably conform to and reflect those assumptions.

Still, some Lutherans seem to be afraid of looking “too Catholic.” Why should this be, though, especially in areas where Catholicism poses zero threat to Lutheran identity? The fact is, we are sometimes more eager to conform to and feel accepted by our many iconoclastic evangelical neighbours than we are to stand strong in our own Lutheran heritage and beliefs. The pervasive influence of popular Christian speakers, books, and media should make us pause and reflect whether the better warning might sometimes be “That’s too Baptist!” rather than “That’s too Catholic!”

C.F.W. Walther puts it in strong terms: “We refuse to be guided by those who are offended by our church customs. We adhere to them all the more firmly when someone wants to cause us to have a guilty conscience on account of them… It is a pity and a dreadful cowardice when one sacrifices the good ancient church customs to please the deluded American sects, lest they accuse us of being papistic. Indeed! Am I to be afraid of a Methodist, who perverts the saving Word, or be ashamed in the matter of my good cause, and not rather rejoice that the sects can tell by our ceremonies that I do not belong to them?”

“We Can’t Afford It”

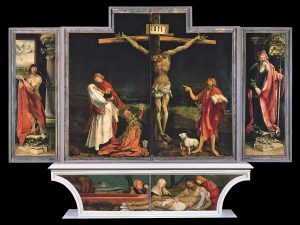

The Isenheim Altarpiece by Matthias Grünewald (c. 1512-1516).

The other main objection to beauty in the church is that art costs money—that we are too poor, or that we need to be feeding the poor instead. The first assertion is generally untrue, and the second presents a false dichotomy. Both statements are a snub to the artist’s vocation.

In general, we are not poor. For people in the West, we have never been richer—and Christians are building uglier, drabber churches than ever. Priority-wise, instant gratification and cheapness seem to frequently win out over transcendence or the glory of God.

When one woman chose to honour and glorify Jesus with aesthetic extravagance in the Scriptures, she was scorned by indignant disciples for the expensive “waste.” Judas Iscariot even accused her of not caring enough about the poor. (Nota bene: St. John informs us that Judas had selfish, not altruistic, motives.) But Jesus defended the woman: “She has done a beautiful thing to me.” He explained the theological significance of the deed—the preparation of His body for burial. Art does both of these: it raises beauty as an offering to God, and points to deeper truths about what He has done.

Let’s not be Judas in our reasoning or practice. We can feed the poor. But art is for the poor, too. Indeed, churches are often one of the few places where the poor can get art and beauty. And many a poor and struggling community have shamed their richer neighbours by the beautiful churches they have raised.

Moreover, art serves an educational purpose too, teaching and reflecting the content of our faith. This was particularly true in the period of the Reformation when many people could not read. Even today, we can learn from and grow in our faith through encounters with sacred art.

Moreover, art serves an educational purpose too, teaching and reflecting the content of our faith.

Consider also the calling of the artist or craftsman. Do we acknowledge that their vocation is legitimate and worthy, as the Bible does (Exodus 31:1-11), or are we implying that their gifts are frivolous and unimportant?

Not every church must be a Gothic cathedral, of course—some churches are less ornamented than others. But when speaking of affordability, a good (and biblical) comparison can be made: our own houses. We can afford those. Do they pale in comparison to our houses of worship? Is it visibly obvious that church is different, set apart, uniquely beautiful—that something happens there that is unlike any other experience on earth—where God comes in His Word and Sacraments to touch us with His forgiving power? Haggai the prophet censured the Israelites for living in “paneled houses” and busying themselves with their homes while the house of the Lord was neglected (Haggai 1). Faith never grudgingly asks God about bare minimums. Faith says: “God’s house, where He is truly present with His gifts, is incomparably precious to me. How can we visually manifest that truth?” Our visuals will confess something. Is it the right thing?

The interior of the Castle Church in Wittenberg, Germany.

What It Means For Us

Neither iconoclastic Protestants nor secularists should be dictating to us what our sanctuaries should be like. A beautifully-adorned church is not inherently “Catholic”– it’s Lutheran. If you have such a church, appreciate and take care of it. And if your congregation decides there’s room for improvement somewhere, in construction or adornment? Before panicking about money, get a few quotes for your project. You may be pleasantly surprised. Think of what will aid your children and grandchildren to regard God’s house with reverence and awe, as a place of truth and beauty, where God is present.

Whatever our churches look like individually, we shouldn’t abandon part of our beautiful, Christ-focused heritage because of mistaken fears about looking “Catholic.” Nor should we hold to a cheap, throwaway approach to faith, and a prioritization of the secular over the sacred.

The architect Duncan Stroik says, “The best churches bring out un‑modern ideas. They remind us of God’s perfection and holiness and make us feel humble.” The Church’s creative heritage has always been counter-cultural. We all need something “out of this world,” stable and transcendent and timeless. We have that in the Gospel. It’s great when our visuals teach the same message.

Kelly Klages is a writer and artist living in Morden, Manitoba.