The Road to Lutheranism

by Robin Dalloo

One of the growing trends in North American church life today is the movement of young people away from Evangelical and Protestant churches for Roman Catholicism or Orthodoxy—or at least that’s a claim often made online. Believing that these two churches are the “original” versions of Christianity, such converts forget the historical reasons for the Reformation and the Gospel truth that the Reformers fought for the freedom to preach. Today, many people see the Reformation and its 500 years of history as mere innovation and as a deviation from the true church. The Reformed theologian Kevin Vanhoozer puts the question many are asking in this way: “Is the Reformation something we should recover, or something we should recover from?”

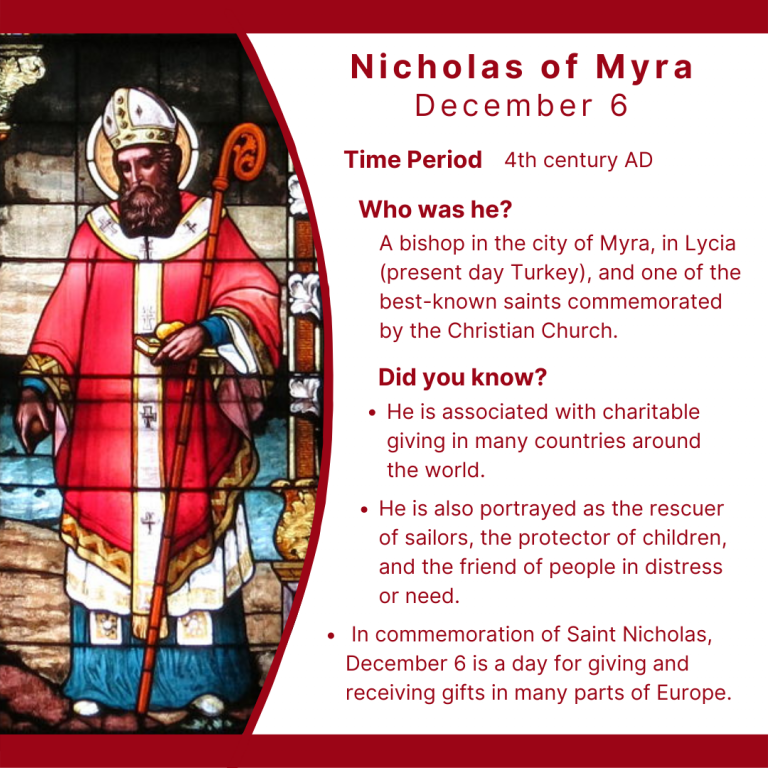

When asked what draws young people to Catholicism or Orthodoxy, most converts do not point to Scripture. Instead, they point to other things: the beautiful architecture of cathedrals or Dante’s poetry, for example, or the mystics and iconography. These things can indeed be beautiful—but making them the basis for conversion demonstrates a believer’s theology of glory. By contrast, Martin Luther preached a theology of the cross that emphasized the sinner coming to know the grace of God in the crucified Jesus.

The Protestant Reformation was not an innovation but rather a movement within the church catholic. As Stanley Hauerwas has said: “Protestantism is a reform movement within the church catholic to make the church catholic truly catholic.”

One of the growing trends in North American church life today is the movement of young people away from Evangelical and Protestant churches for Roman Catholicism or Orthodoxy—or at least that’s a claim often made online.

I was raised in a non-denominational church and began studying theology at the age of 18. Many of my friends and I who were studying philosophy and theology eventually came to the conclusion that there were too many philosophical contradictions in Protestantism (at least as we understood it). We thought that Orthodoxy or Catholicism were the true expressions of historical Christianity. At age 24, as a result, I was received into the Roman Catholic Church. Many of my friends also joined Catholicism around the same time.

I embraced a Catholic prayer and devotional life for many years; but as someone who was not raised in the tradition, I found I had to reckon with the things I was now doing and saying. For example, I began praying for souls in Purgatory—but my conscience was not at peace. I felt I had gone too far. I remembered the Reformation’s rallying cry against the practice of works righteousness and unbiblical teachings like Purgatory.

In time, I became acquainted with some Lutheran pastors and lay theologians. I returned to belief in the importance of justification by faith. Eventually I made a profession of faith and was received into Lutheran Church–Canada in 2019.

In time, I became acquainted with some Lutheran pastors and lay theologians. I returned to belief in the importance of justification by faith. Eventually I made a profession of faith and was received into Lutheran Church–Canada in 2019.

It shouldn’t be surprising then to learn that today I no longer believe that the Reformation is something we should repent of or seek to reverse. As the saying goes, “semper reformanda, secundum verbum Dei”—the church is “always reforming, under the Word of God.”

Many Roman Catholic apologists and their followers in conversion culture view the Reformation as something that “split the church.” They cite overblown (and misunderstood) statistics on how many Protestant denominations supposedly have sprung up in the name of sola Scriptura (“Scripture alone”). To have true unity in the Church, they argue, we must all be under the Pope. For this, they cite Matthew 16, which they interpret as Jesus making Peter the first Pope. They also cite John 6, and connect apostolic succession with a valid Eucharist. According to them, only churches in communion with the Pope offer such a valid Eucharist.

What they fail to see in these texts is that Scripture is more open in its catholicity. Does not our Lord say that wherever two or three are gathered in His name, He is there (Matthew 18:20)? Limiting the Church to only those bodies in communion with the Pope then is to reduce the church catholic—the church universal (which is what “catholic” means)—to mere institutional catholicity. It fails to leave room for the Holy Spirit’s work in the preaching of the Word of God outside Roman Catholic walls.

As for those other things which young people sometimes point to as a reason to convert—the beauty of Catholic liturgy, for example—we should remind them the Lutheran Church also has a deep and rich liturgy following the pattern of the church historic.

Putting aside the questions of apostolic succession and the Pope, the main issue in dispute between Roman Catholics and Protestants remains justification. This was the major issue during the Reformation, and it is still the centre of disagreement today. In the 16th century, the Catholic Church countered the teaching of Martin Luther and the other Reformers, arguing at the Council of Trent that we are justified by faith and works together. They indeed taught that we are justified through Christ and that this grace is infused into the believer’s soul. But they said that this grace is given as an aid to virtue. Ultimately, they argued, believers will be judged on the measure of grace and virtue in their souls. Baptism introduces us to divine life, and more of this life is poured into the soul through the Sacraments; but ultimately, the believer will be judged on the basis of their own virtue.

By contrast, the Lutheran position is that we are justified through an “alien righteousness”—which is to say, not through our own righteousness but through a righteousness from outside of us: through Christ’s righteousness. The cross and resurrection are salvific; they are not just an outpouring of divine life but the very instruments of our salvation. The work that Christ did on the cross is imputed to us. He receives our sin, and we receive His alien righteousness. It comes to us extra nos—from outside of ourselves. It isn’t our works that save us; it’s Jesus. Those considering leaving their church home for another should reflect long and hard on the issue of justification.

As for those other things which young people sometimes point to as a reason to convert—the beauty of Catholic liturgy, for example—we should remind them the Lutheran Church also has a deep and rich liturgy following the pattern of the church historic. We sing beautiful chorales, many churches still sing polyphony, and we use musical settings composed by master composers like Johann Sebastian Bach. It is certainly true that some Protestant church bodies do not have a rich liturgical heritage; but there is a wealth of beauty and tradition in the Lutheran tradition.

At the same time, our tradition is rooted in Scripture, and our devotional practices flow from a theology inspired by Scripture. Some converts to Catholicism and Orthodoxy are attracted to the idea of mysticism—to the suggestion they might experience supernatural revelations from God. But God promises no such experiences in His Word. If we seek mystical experiences for their own sake, we can fall into the danger of treating our own thoughts and imaginings as more important or authoritative than God’s Word.

We must remain rooted in Scripture. The Reformers held fast to this teaching, and their Scripture-based understanding of the Gospel—that we are justified by faith alone in Christ—remains relevant today and always. We must not depart from this Gospel that we have received.

As children of the Reformation, we should reclaim our identity as people who seek the Truth and are not afraid of controversy. Theological reflection is not new to Lutherans, and we rightly delight in our Lutheran Confessions. As a result, we should welcome modern conversion culture—as Evangelicals and other Protestants look for a deeper connection to the Church historic—as a new opportunity to preach the Gospel. Our preaching and worship should reflect the joy of salvation that comes not from our own works, no matter how beautiful or intellectually appealing they may be, but instead from the crucified Saviour, who welcomes sinners. Grace comes from outside of ourselves through Christ, not through our institutional affiliation with a specific church body. The preaching of God’s Word creates the community of faith. Christ Himself calls His flock.

“Christ alone our souls will feed; He is our meat and drink indeed; Faith lives upon no other.” So writes Martin Luther (LSB 458:7). Our communion is not merely with an earthly institution, but instead with Christ, with His Father, and with the Holy Spirit. Where this truth is taught clearly, the true Church is truly present.

—————

Robin Dalloo is a writer with a Master of Divinity degree living in Winnipeg.