Black Adam: Triumphantly Average

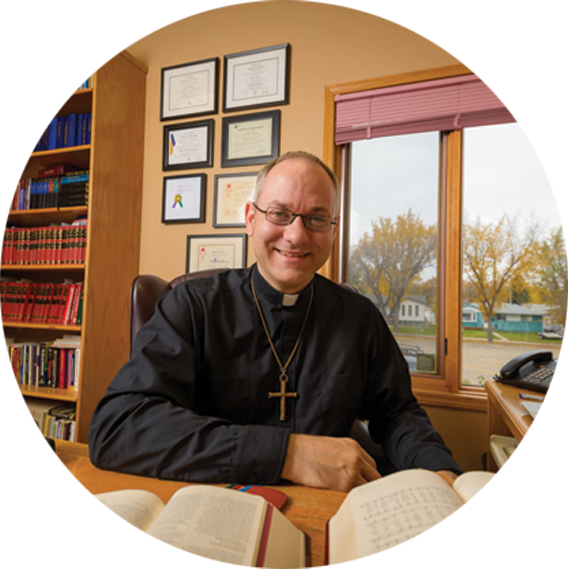

by Ted Giese

by Ted Giese

Black Adam is a DC film that tells the story of a modern-day return of a virtually indestructible champion Teth-Adam (Dwayne Johnson). Teth-Adam had been entombed for five thousand years following an ancient conflict with a tyrannical king, Anh-Kot, over the control of a crown with the power to open the gates of hell. When the crown is discovered by archeologist Adrianna Tomaz, the last descendant of Anh-Kot, Ishmael, tries to get it for himself. Teth-Adam—dubbed Black Adam by the end of the film—returns to save the Middle Eastern nation of Kahndaq from becoming an open gate to hell. This garners the attention of a ruthless covert American government official, Amanda Waller, who sends in members of The Justice Society of America to kill or capture Black Adam and neutralize the threat she believes he presents to the world. The people of Kahndaq meanwhile—currently oppressed by an organized crime syndicate called Intergang—simply want their champion to save them so they can live in peace.

General audiences might not be familiar with the character of Black Adam. In this film, Black Adam received his powers from the same council of wizards that granted mystical superpowers to the teenaged foster kid Billy Batson in 2019’s Shazam film. But in the comics, Black Adam originally appeared as an ancient Egyptian super-villain in the first issue of The Marvel Family in 1945. Over the past twenty years, the character has been rehabilitated into a kind of anti-hero; anyone who stopped reading comics more than twenty years ago might be surprised then to find Black Adam as a hero in this film! But the film makes an attempt to explain the rougher nature of Black Adam’s sense of justice, revealing that Black Adam’s powers were originally intended to go to his more virtuous son, who tragically died by the order of Anh-Kot. This revelation helps the audience find Black Adam more relatable while also explaining why he’s a short-tempered juggernaut filled with grief and rage.

As a character out of the past, Black Adam is certainly a “fish out of water” character in this film, with different views of how the world should work and how vengeance and justice should be enacted. As might be imagined with Johnson filling the role, Black Adam exudes masculinity and gravitas—something less common today in today’s treatment of superheroes, which tends to upend male characters with female characters. This is not the case in Black Adam. For example while the archeologist Adrianna Tomaz who finds the mystical Crown of Sabbac of this film is not exactly a damsel in distress, she is also not played as masculine and is allowed to display feminine attributes; she is even a mother with all the concerns that brings with it. She is initially unsure what influence the brute masculine nature of Black Adam might have on her son but eventually embracing the pragmatic necessity of his raw power in the face of destruction.

While presented as a hero, Black Adam retains some of his anti-hero nature. He is confronted at one point by Hawkman, who says, “In this world, there are heroes and there are villains. Heroes don’t kill people!” Black Adam replies, “Well, I do.” Black Adam doesn’t hesitate to kill his opponents, and where other superhero films might have hordes of CGI aliens, robots, or demons for the heroes to dispatch, many adversaries in Black Adam are men with military equipment: soldiers, mercenaries, and gang members. The film presents Black Adam as a violent super hero fighting violent men, while also suggested that this violent nature is generally unacceptable in the modern world—a force that needs to be tempered with a justice that values life.

Committed fans of the Black Adam character will likely be able to look past the predictability of the plot, but you average viewer may be a bit bored with the set-up and pay-offs in this film. As with other films in the DC franchise, this movie sees a team of heroes band fight an apparently threatening adversary (Black Adam) only to band together in the third act to defeat a far greater threat: the demonic Sabbac. There can be comfort in predictability, of course. But with the wide assortment of superhero films available today, compelling storytelling becomes increasingly important to stand out in the crowd. In some ways Black Adam suffers from feeling too familiar—and, as the ancient adage goes, “familiarity breeds contempt.”

How should Christians response to these sorts of themes in real life—to magic, to violent revenge, to questions of life and death, and so on?

What is a Christian to think of Black Adam? On the surface, there is the question of the role of violence in working out justice. This is one of the film’s themes. In some ways, Black Adam could be seen as a sort of Old Testament judge like Samson: flawed but powerful. He could even be thought of in the vein of “Master Hans,” the executioner from Luther’s Large Catechism— a man with the vocational responsibility to carry out justice on the wicked. The disposition of such a man, whether he is kind or harsh, wise or foolish, makes little difference provided he sticks to carrying out his vocational responsibilities and doesn’t go astray. For his part, Black Adam is a man who needs to manage his rage and deal with his underlying grief. Christians will recognize his need to grow in self-control, which is a gift of the Holy Spirit (2 Timothy 1:7).

The more challenging aspect of Black Adam for Christians is how he is presented as a kind of demigod. At one point, Dr. Fate says to him, “We know who you are and what you are capable of. There’s no place for you in the world of man. You have two choices: kneel or die,” to which he replies, “I was a slave until I died. Then I was reborn a god. I kneel before no one.” Add to this is the notion that he is a long-awaited messiah who returns to work justice against the wicked, and Black Adam becomes a kind of millenarian figure. But unlike the Jesus Christ confessed by Christians as the only begotten Son of God, Black Adam fits into the category of apotheosis, where an individual is raised up to godlike stature not by a god but by wizards. When compared to Scripture, this makes him into a kind of anti-Christ.

Another esoteric element in the film is the inscription on the inside of the Crown of Sabbac that reads: “Life is the only way to death.” By the end of the film, the phrase is inverted to read, “Death is the only way to life.” Does it really mean anything or it just nonsense dialogue intended to sound deep? The film is also filled with talismans, magical objects, and esoteric symbolism, including inverted pentagrams, a pyramid hand gesture, and more. Much of these details and esoteric oddities are lost between explosions, bolts of lightening, and punches, but it’s okay for Christians to ask what their inclusion is intended to convey, if anything.

How should Christians response to these sorts of themes in real life—to magic, to violent revenge, to questions of life and death, and so on? Scripture is of course clear. Christians should avoid the occult (Exodus 7:11; Leviticus 20:27; Deuteronomy 18:10-12; 2 Kings 21:1-9; Micah 5:12-15; Isaiah 47:12-15; Ezekiel 13:18, 20; Acts 8:11-24; Revelation 9:21; 22:15). The average Christian does not have the vocation to use violence to solve problems but must instead leave vengeance in the hands of God (Deuteronomy 32:35; Romans 12:19). And Christians are to put their faith and hope for eternal life in Christ Jesus, who heroically defeated death and is our very life (Revelation 1:18). And the returning heroic champion Christians are waiting for is not a Black-Adam-like figure but Christ Jesus (Acts 1:11).

Christians can praise the film’s strong masculine and feminine characters, as well as some positive depictions of traditional family relationships and traditional relationships between men and women (as well as the absence of culturally divisive progressive gender ideology). But the film’s overall narrative still struggles to rise above mediocrity. If it weren’t for the skill and charismatic appeal of Johnson as Black Adam, the film would dissolve into forgettable nothingness. In short, it’s not the worst of this kind of film but neither is it the best; it’s more average than anything else.

Christians can praise the film’s strong masculine and feminine characters, as well as some positive depictions of traditional family relationships and traditional relationships between men and women (as well as the absence of culturally divisive progressive gender ideology). But the film’s overall narrative still struggles to rise above mediocrity. If it weren’t for the skill and charismatic appeal of Johnson as Black Adam, the film would dissolve into forgettable nothingness. In short, it’s not the worst of this kind of film but neither is it the best; it’s more average than anything else.

———————

Rev. Ted Giese is lead pastor of Mount Olive Lutheran Church, Regina, Saskatchewan, Canada; a contributor to The Canadian Lutheran, Reporter; and movie reviewer for the “Issues, Etc.” radio program. For more of his television and movie reviews, check out the Lutheran Movie Review Index.