More than Enough: The Miracles of Jesus

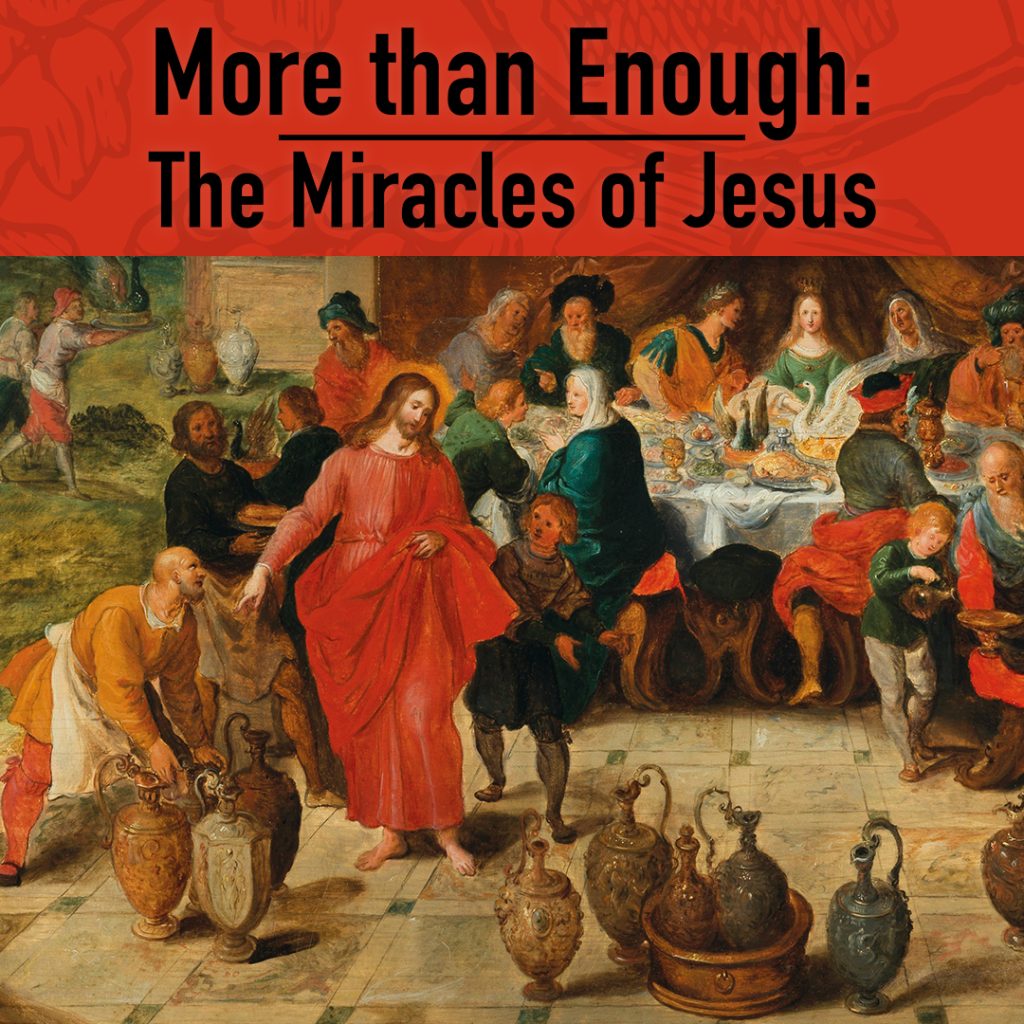

“THE MARRIAGE AT CANA,” detail. The Workshop of Frans Francken II, before 1637.

by Jim Chimirri-Russell

The first and great enemy is scarcity. From the second that humanity fell into sin and the fall occurred, then scarcity began. Before that moment, there was no such thing as scarcity. No such thing as want. Things have changed so much since then that scarcity is now seen by us as a fact of the universe—when it wasn’t supposed to be. In the beginning, there was no scarcity. No want. There was no concept of there not being enough. Food was plentiful and easy to attain. There was no sickness, no disease, nor any concept of plants or animals having to defend themselves. What you wanted, you could have.

Then, the fall. Then, scarcity. Then, humanity found itself facing scarcity of every kind: of food, of health, of time, of all of it. Humanity came to understand that, from this point on, effort was going to govern how we lived. Effort—the sweat of our brow—was the way that we would stave off the scarcity. But there was still never going to be enough. The concept of “enough”—enough for everyone—just no longer existed.

What makes the works of our Lord, Jesus Christ, when He appears on the scene, so miraculous is that they address and defeat the concept of scarcity. What makes them so miraculous is that the scarcity which had governed the human race since the fall was now met with the abundance of paradise.

When Jesus shows His mastery over the elements of this earth, He is showing the people what it is like to live in the presence of God, where needs are actually met, questions answered, and there truly is enough.

When people encounter Christ, they see, even if just for a moment, what it must have been like in the garden. When Jesus shows His mastery over the elements of this earth, He is showing the people what it is like to live in the presence of God, where needs are actually met, questions answered, and there truly is enough.

Consider the first miracle of our Lord at the wedding at Cana in Galilee. What is the problem the people were encountering? They have no more wine. There is not enough wine for their needs. This is the very definition of scarcity. There is a want, a desire, but no way to meet that desire. When Jesus addresses the situation, He doesn’t call into existence a new creation. Instead, He shows the people at the wedding what it is like to want something and be able to actually have it. He shows them, in other words, what it means to not run out of things.

We have been so accustomed to the concept of scarcity that we act as though running out of something is absolutely going to happen. No matter how much wine you have for your wedding, you can and will inevitably run out. If the party goes on for long enough, then you will, by definition, run out of wine. There is not enough wine you can buy to make sure that you will always have enough. You can have enough wine for one gathering, but it will not be enough for every possible future gathering. You will have to buy more or make more—and that will take work.

“MULTIPLICATION OF THE LOAVES AND FISH,” Ambrosius Francken, 1598

And yet, when the water becomes wine, it does so without any labour or effort on the part of the people who are at the wedding. The guests, the host, the happy couple… none of them had to expend any work, sweat, or labour to get that wine. The scarcity of that moment is defeated by the abundance of Christ.

The feeding of the 5,000 works in a similar fashion. In the Gospel of John, when there is a big crowd surrounding Jesus and they are clearly hungry, the discussion that Jesus has with Philip is not just about hunger but also about work. Philip, as with the rest of us, has tied food to effort—a reality we all experience since the curse; by the sweat of our brows will we eat our bread (Genesis 3:19). And so, when faced with such a massive crowd, the concern from Philip was this: not just how much money it will take but how much work it will take to feed everyone. “It would take more than half a year’s wages to buy enough bread for each one to have a bite” (John 6:7 NIV). The problem isn’t that bread doesn’t exist but rather that both there isn’t enough—and there isn’t enough time to make enough money to buy it.

When Jesus has the people sit down and begins to feed them from one boy’s lunch, He separates the food from the work. The people who are there are free to eat without working, fulfilling the promise from the book of Isaiah: “He who has no money: come, buy and eat!” (55:1). It is so foreign to our understanding of the universe to contemplate the abundance of God in the way that it was supposed to be: that food would be completely disconnected from effort. But this is what we see in the miracles of Christ.

The greatest of all of Jesus’ miracles is certainly the raising of the dead. This is something that defies not just the natural order but the very governing principles of how we function as human beings—the life we live with a ticking clock in the background all the time. The concept of the eternal runs head-on with the finite nature of the world in which we live. Life and death teach us that it hurts to lose those whom we love. And to go on without them is a difficult thing, for it puts the desire for eternity within our hearts while leaving it eternally outside of our reach. The great scarcity is simply this: you are dust, and to dust you shall return.

“THE RAISING OF LAZARUS,” detail. Rembrandt, c. 1630.

Of all the things that there is not enough of, time is the first and foremost. All other scarcity hinges upon this one. You could work more, buy more, do more—except that there is literally never enough time. The grief felt by Jairus and his family over the death of his daughter is simply this: they had run out of time—time itself was scarce, and they had run out of it.

Once time runs out, you can’t buy more. No additional work, no additional effort can produce more of it. The eternity at the beginning of everything situated Adam and Eve in a space where time did not run out, a concept that we both can’t imagine and yet seem to be built for. None of us live a life where we behave as though the people around us are on the way out. We get desperately, hopelessly attached to one another as though eternity was a guarantee. And all the while, time keeps running out.

When Jesus raises Lazarus from the dead, though he had been dead already for four days, He undoes the greatest scarcity of all. He makes more time where there was none left. Can you imagine a world where time wasn’t running out? Where you would always have enough time—enough time for all of it? Where you could spend all the time you could want with those you love, where you would finally have time to get to everything you wanted? A world where the hard stop of time was itself removed? That’s what the world was supposed to be in God’s original design. When Jesus raises people from the dead, He shows what it means to live in a universe the way God had intended—where we are not governed by things running out but simply live in a universe where there is actually enough.

When Jesus raises Lazarus from the dead, though he had been dead already for four days, He undoes the greatest scarcity of all.

You don’t need to just imagine it. Through His own death and resurrection, Jesus welcomes us into that universe of enough. Wiping away our sin, wiping away the curse, He gives us instead new life. His life. Life that truly lasts to eternity.

What are the miracles of our Lord then? Simply put, they are ways in which God gives us glimpses of a world with the curse undone—a world where needs can be met and the love of God is manifest. What would it mean to live in such a paradise? Simply this: living in a world where things don’t run out, and where there is enough for all.

———————

Rev. Jim Chimirri-Russell is pastor of Good Shepherd Lutheran Church in Regina, Saskatchewan.