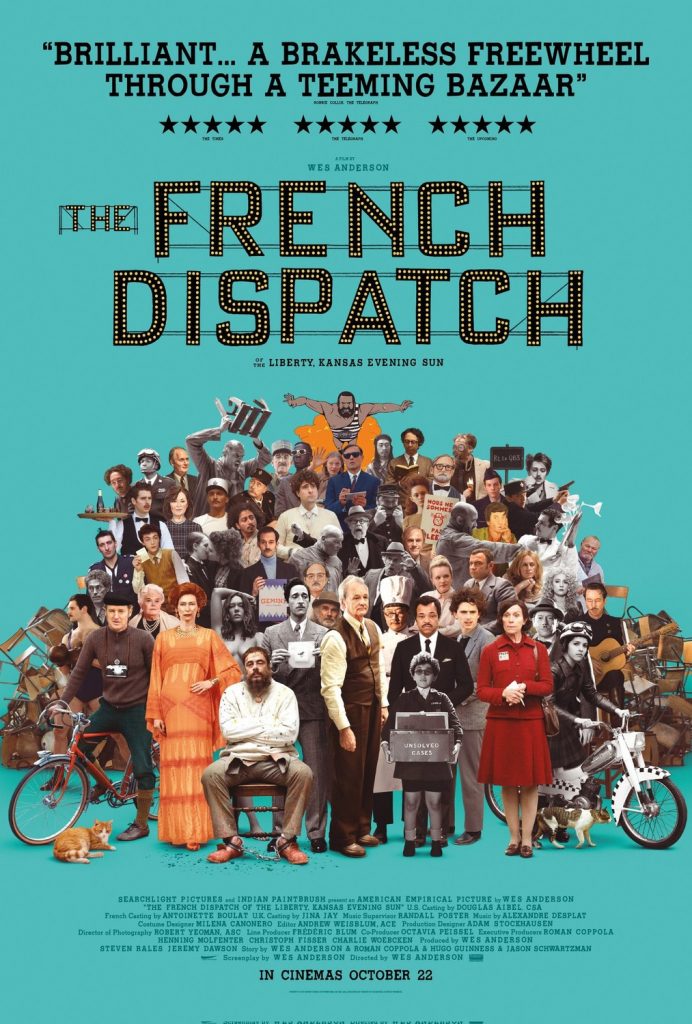

The French Dispatch: Colourful, Obsessive Show-and-Tell

by Ted Giese

by Ted Giese

Set in the fictional French town of Ennui-sur-Blasé, Wes Anderson’s The French Dispatch chronicles the publication of the last edition of “The French Dispatch,” a supplement in a fictional New Yorker-style magazine called the Evening Sun. The magazine is headquartered in Liberty, Kansas, and its editor-in-chief is Arthur Howitzer Jr., son of the magazine’s owner.

As a young man, Howitzer Jr. traveled to Europe and convinced his father to include some reports from abroad as a supplement to the publication. Howitzer Jr ended up spending his career in France, attracting an eclectic stable of journalists and bohemian writers who adore and respect him. In classic authoritative Anderson style, the narrator declares, “He brought the world to Kansas”—but by the time the credits roll, it’s clear that Arthur Howitzer Jr. also brought a little bit of Kansas to France. While generous toward and supportive of his writers, Howitzer has a no-nonsense motto painted on his office wall— “No Crying”—alerting viewers to a kind of west-meets-midwest ethos which permeates his publication.

Presented as an obituary, with a travel guide and three brief features, the film loosely follows the magazine’s structure. The obituary is for Arthur Howitzer Jr., who upon his death in 1975 disbands the magazine, making the current issue its last. The travel guide, written by cyclist reporter Herbsaint Sazerac, introduces viewers to the town of Ennui-sur-Blasé. Anderson presents this reportage in a split screen, showing locations both in the past and their present, signalling to the audience that the more things change the more they stay the same. Christian viewers may think of this sentiment’s source: “What has been is what will be, and what has been done is what will be done, and there is nothing new under the sun” (Ecclesiastes 1:9).

Anderson’s approach is a sort of open invitation for viewers to enter into the unfolding story with their own experiences and feelings while simultaneously holding viewers at arm’s length with his tableau vivant chocolate box style and obsessive attention to detail in both the visual and expository aesthetic of the story.

In this way, Anderson’s approach is a sort of open invitation for viewers to enter into the unfolding story with their own experiences and feelings while simultaneously holding viewers at arm’s length with his tableau vivant chocolate box style and obsessive attention to detail in both the visual and expository aesthetic of the story. This quirky interplay of the familiar and the offbeat taps into comforting nostalgic feelings for a time beyond the viewer’s life experience and locale. It approximates the experience of wandering through an art gallery, where the occasional portrait or historical painting includes a familiar face, while at the same time shutting the viewer out. As Sazerac the travel guide writer says, “All great beauties withhold their deepest secrets.”

Each of the three brief “feature articles” could be their own film but are presented as an anthology linked by their French Dispatch reporters and the setting of Ennui-sur-Blasé. The first feature article “The Concrete Masterpiece” by arts and culture correspondent J.K.L. Berensen revolves around a psychologically disturbed inmate convicted of murder, Moses Rosenthaler, and his muse, the prison guard Simone, who oversees the prison’s arts and crafts room. When an incarcerated art dealer Julian Cadazio happens upon Rosenthaler’s work he goes about transforming the unknown artist into an international sensation garnering the interest of Kansas art maven Upshur ‘Maw’ Clampette, whose assistant is a young J.K.L. Berensen. Rosenthaler’s shining achievement is a series of abstract nudes of Simone painted as frescos into the concrete walls of the Ennui-sur-Blasé prison perfectly illustrating desire: Rosenthaler loves Simone but cannot truly have her. His paintings, not on canvas but permanently on the walls of the prison, make them an art dealer’s object of desire which is equally hard to obtain.

Lutherans in particular would see any valid application of forensic justification centred only upon the merits of Christ Jesus, not upon the merits of the individual.

Christian viewers may be especially interested in a brief scene where Rosenthaler sits before a parole board in what looks like a former French gothic church. The art dealer Cadazio addresses three magistrates who sit flanked in profile by Christian crosses emblazoned on the stone walls. He admits Rosenthaler is clearly insane and guilty of his crimes, but he is certainly also an artistic genius so, “Surely there ought to be a double standard for this kind of predicament?” His appeal is based on a balance of merit. Lutherans in particular would see any valid application of forensic justification centred only upon the merits of Christ Jesus, not upon the merits of the individual. Cadazio, sitting across from the three magistrates with Rosenthaler set between them, is also flanked in profile by Christian crosses on the stone walls. These obvious symbols haunt this scene, depicting Rosenthaler as a man caught between forgiveness and damnation.

The second feature “Revisions to a Manifesto” by embedded political journalist Lucinda Krementz is the weakest of the three articles. It deals with Krementz’s personal entanglement with student activist Zeffirelli. In lieu of a more age-appropriate coupling with Paul Duval, Krementz engages in a sexual relationship with the young Zeffirelli as she likewise transgresses the line between journalism and activism by proofreading and revising his student manifesto. Under the slogan “The students are grumpy!” the students are protesting against the university and the town for the right of male students to gain free access to the women’s dormitory.

Imagine a world where practical restrictions on students promoting diligent study and a moral lifestyle are enforced for the common good: the mind boggles! The fact that this restriction makes them “grumpy” enough to riot in the streets would seem quaint considering the current state of student life and the perpetual issue of youthful inclinations towards unchastity. As Krementz opines, “The kids did this, obliterated a thousand years of republican authority in less than a fortnight. What do they want? Freedom. Full stop.” But freedom from what? Apparently, freedom from a sexually pure and decent life. While Krementz is presented as a jaded journalist, in truth she is as immature as the students she is embedded with and has not matured to the point of praying, “Remember not the sins of my youth or my transgressions,” (Psalm 25:7).

The third feature “The Private Dining Room of the Police Commissioner” by food critic and essayist Roebuck Wright follows events resulting from the interruption of a private dinner hosted by Ennui-sur-Blasé’s Chief of Police. The Commissioner’s son Gigi is kidnapped by a gang of hired thugs who want to exchange him for an arrested mob bookkeeper, Albert ‘the Abacus’. Roebuck, intending to write about the Commissioner’s chef Lieutenant Nescaffier, finds himself embroiled in the plot unfolding around him. After an armed standoff with the police, the lead kidnapper, referred to as The Chauffeur, relents and allows Lt. Nescaffier to prepare a snack for Gigi and a meal for the kidnappers. This eventually leads to a line of dialogue from Nescaffier to Roebuck about the taste of one of the ingredients in the meal he prepared for the kidnappers, which leaves him “seeking something missing, missing something left behind.” The two bond over their shared experience of being foreigners in France,, and Roebuck and Nescaffier’s melancholic tale of regret finds comfort in the hospitality rituals and culinary structures of cooking and dining.

The core of Roebuck’s story is kindness. For different reasons, Roebuck and Albert ‘the Abacus’ had shared a jail cell called ‘the chicken coop’ at the Ennui-sur-Blasé police station. Some graffiti in the cell indicates Roebuck was there first. Where Albert’s planned escape involved a kidnapping plot and using force, Roebuck was sprung by the kindness of The French Dispatches’ editor Arthur Howitzer Jr., who conducts Roebuck’s job interview separated by the chicken wire cell walls. Howitzer hires the versatile writer with the same advice he gives all his writers, “Try and make it sound like you wrote it that way on purpose.”

Howitzer’s kindness paved the way for Roebuck to receive the assignment to review the police cooking of Lt. Nescaffier, moving him from the jail cell to the Commissioner’s dinner table. Roebuck’s initial incarceration was due to his homosexuality. Anderson here is endearing the audience to the character in a much more subtle way than normally found today in Hollywood. Apart from his poor sense of direction—he calls it “a weakness in cartography, the curse of the homosexual”—the fact that Roebuck is gay is downplayed throughout his segment of the film and is presented as somewhat unimportant to his work as a reporter.

One has to ask: how much more Wes Anderson can Wes Anderson go before he has gone too far in his precious and obsessive film making style?

The name of the fictional town Ennui-sur-Blasé is the key to the film: ennui is a noun which means a feeling of listlessness and dissatisfaction arising from a lack of occupation or excitement, while blasé is an adjective which means a feeling of being unimpressed or indifferent to something because one has experienced or seen it so often before. These French words denoting boredom-upon-apathy provide the perfect backdrop for Anderson’s vignettes of complicated desires, immature concupiscence, and melancholic regrets. They also provide for the thematic foil of grace towards the broken Rosenthaler and kindness toward the lost Roebuck. The name also illuminates the film’s art direction, serving as the bedrock upon which Anderson uses both colour and black and white imagery, artfully switching back and forth between the two styles to emphasize the juxtaposition between the mundane and the exciting.

Ennui and blasé further serve as a kind of meta commentary on Wes Anderson’s film making. This is his tenth feature film and Anderson seems to be at peak Anderson. One has to ask: how much more Wes Anderson can Wes Anderson go before he has gone too far in his precious and obsessive film making style? For some viewers who have watched a number of Anderson’s films, The French Dispatch may leave them feeling unimpressed or indifferent because they will feel they have seen it all before—that there is nothing new under the sun, with this film just a kind of further-refined and distilled rehash of The Grand Budapest Hotel. Others who come to Wes Anderson for the first time will find a kind of quirky exuberance, something akin to listening to a Grade 4 show-and-tell where the kids excitedly tell you everything about the object they brought to class. To some this approach is exhausting; to others it’s exhilarating.

Perhaps The French Dispatch is intended to be a remedy for the listless dissatisfaction many find in the current paint-by-number dumbed-down block-buster film-factory approach to storytelling and filmmaking. This will not be to everyone’s liking, of course; Anderson is an acquired taste. Most people, after all, enjoy one or two fancy selections from an assorted box of chocolates, but The French Dispatch is like eating all the chocolates in one sitting and then being asked to eat the box! For those willing to be swept away in the colourful albeit eccentric illustrative story which Anderson delivers there is both aesthetic fun and worthwhile ethical quandaries to ponder. For those who love Anderson there is a lot to love.

Perhaps The French Dispatch is intended to be a remedy for the listless dissatisfaction many find in the current paint-by-number dumbed-down block-buster film-factory approach to storytelling and filmmaking. This will not be to everyone’s liking, of course; Anderson is an acquired taste. Most people, after all, enjoy one or two fancy selections from an assorted box of chocolates, but The French Dispatch is like eating all the chocolates in one sitting and then being asked to eat the box! For those willing to be swept away in the colourful albeit eccentric illustrative story which Anderson delivers there is both aesthetic fun and worthwhile ethical quandaries to ponder. For those who love Anderson there is a lot to love.

———————

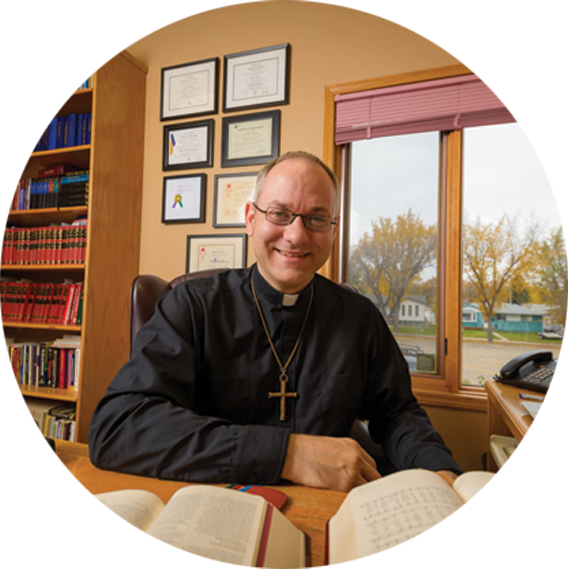

Rev. Ted Giese is lead pastor of Mount Olive Lutheran Church, Regina, Saskatchewan, Canada; a contributor to The Canadian Lutheran, Reporter; and movie reviewer for the “Issues, Etc.” radio program. For more of his television and movie reviews, check out the Lutheran Movie Review Index.